The development of rifled cannon changed the face of warfare forever. Most notably it made the concept of brick and stone fortifications obsolete. With greater accuracy and power, field artillery could now do the job of larger smooth bore weapons.

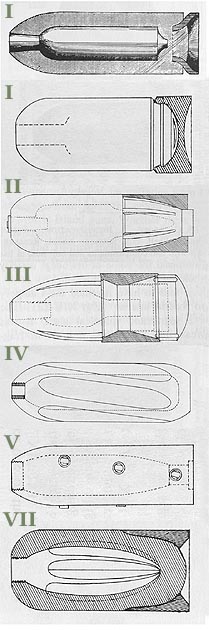

Civil War era rifled projectiles come in a bewildering variety of types and variations, but all were designed to engage the rifling while in the cannon barrel which spun the projectile as it left the muzzle. How that was best achieved was a matter of diverse opinion.

To simplify identification, artillery can be classified into basic groups, each according to the way each shell's design engaged the rifled barrel.

The inventor's name often became associated with theses rounds. Here is just a quick reference, not intended to be all inclusive, but just to give a general idea.

| Diagram |

Features |

Name |

| I | Driving Ring / Cup Fixed to Base | Read, Parrott, Dahlgren, Dyer, Mullane, Brooke, Absterdam |

| II | Lead or Paper Covered Splined Base | (Lead) James, Archer (Papier-Maché ) Schenkl |

| III | Two-Part w/ Center Band |

Hotchkiss, Gorgas |

| IV | Projectile / Bore Matched Shape |

Whitworth |

| V | Studded, Ribbed or Grooved |

Sawyer, Rodman, Blakely, Armstrong |

|

|

Lead Covering |

Armstrong, Sawyer |

| VII | Misc |

Burton, Abbot |

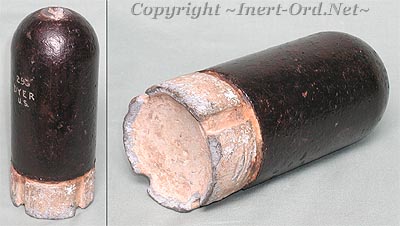

The Hotchkiss patent was for a projectile consisting of three main sections. When fired, the moveable base compressed

a central lead band, pushing it outward squeezing it into the rifling.

The Hotchkiss patent was for a projectile consisting of three main sections. When fired, the moveable base compressed

a central lead band, pushing it outward squeezing it into the rifling.